Blog Article

Curated by Jiang Jiehong

Artists include HAN Kyung-woo, HUANG Fangling, HU Jieming, LIU Jianhua, PENG Wei, Yuma TOMIYASU, YIN Yi and ZHAN Wang.

In the last four decades, China has seen the most extraordinary economic growth, fuelled by rapid urban development, the scale and speed of which are unprecedented in human history, particularly with regard to the increase in construction projects. Buildings, architectural complexes, streets, and even whole cities can be transitory, leaving little trace of what has gone before. At the same time, more attention should be given to the intangible processes of transformation, such as how individual urban residents experience and perceive their changing cities through cultural means, for a more holistic and multifaceted understanding of urban aspiration and its consequences in China. Urban changes have never ceased since the ‘revolutions’ in the last century, and are evident in the acceleration of economic development since the Reform and Opening Up policy (1978), shaping a moving reality, beyond the normal and perceptible daily experience.

Amongst the forest of skyscrapers in Lujiazui, there is a large detached house in a traditional style of Chinese architecture, which is currently called the Wu Changshuo Memorial Hall (WMH). In comparison with all the modernised (or Westernised) high-rise buildings that populate the area – with their minimalistic glossy or matt structures, their neon lights and giant LED screens and façades – it appears to be antiquated, solitary, and isolated from everyday life. As one of the oldest existing buildings in the city, it has survived the turbulence of wars, and political movements of the past century, and it has witnessed the dramatic urban transformations in post-Mao China. To understand the country’s revolutionary urbanisation and its social and cultural impacts, this project focusses on this uniquely surviving heritage building in Shanghai.

Originally, the Yingchuan Villa (as it was once known) was privately owned by the successful entrepreneur Chen Guichun (1873–1925). Starting in 1914, the construction of the Yingchuan Villa was completed in 1917, at which point it was one of the most luxurious mansions of its time. It then became a gathering place for Shanghai artist celebrities and intellectuals, including Wu Changshuo, one of the leading figures of the Shanghai School. After Chen Guichun passed away, his business declined, then his family members fled from the house in terror after Japanese forces began the Battle of Shanghai in August 1937. The Yingchuan Villa was occupied by Japanese troops as the Headquarters of Japanese Military Police during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), and then by the Nationalist Party as the National Garrison Command until 1949. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it was used for different purposes: as a printer’s premises, as a tanning workshop, and as a tax revenue office in the 1950s. From then on, it was reconstructed, with existing rooms being partitioned for distribution to local people and to accommodate many more residents. In the late 1990s, alongside the urban development in Pudong, the building was reconstructed as a showroom to promote the latest achievement in Lujiazui. Consequently, in 2010, it was repurposed again, as today’s WMH, not only to commemorate Master Wu Changshuo and to celebrate his influential achievements, but also to showcase Chinese arts and culture to an international audience. With both traditional craftsmanship and then-advanced technology, the building features a combination of Eastern and Western aesthetics. Significantly, the villa houses the most exquisite wood carving decorations, which appear prevalently throughout the building and have earned it its reputation as the ‘Pudong Mansion of Carved Patterns’.

In this exhibition, The Sleepless Theatre, the notion of the ‘theatre’ has three tiers of meaning. First, it refers to the building itself. On the one hand, its exceptional interiors, especially the wood carvings of idiomatic narratives, folk plays and classic works of Chinese literature, can be seen as a series of frozen dramas, and on the other hand, the building has acted as a theatre of everyday existence, with its quality of temporality and fluidity, over the multiple generations of residents. Second, its location at the heart of the financial centre of Shanghai is also like a theatre set. Unlike old areas in the city that feature the shikumen (literally, stone gate) architectural style and typical nongtang alleyways, Lujiazui, developed in a matter of a couple of decades, has become crowded with modern office blocks and shopping malls with glass curtain walls. While Lujiazui has rapidly become an economic, cultural and touristic landmark, it is detached from personal memories of daily life in Shanghai. From the WMH courtyard, one can see an almost surrealistic scene – the three tallest buildings in Shanghai, namely, Jinmao Tower, Shanghai World Financial Centre and Shanghai Tower, penetrating the sky beyond the flying eaves of the traditional building. This stages a dramatic dialogue between the vigorous and the tranquil, and between the past and the present. Third, the city of Shanghai itself has become a world theatre. While travelling between globalised urban sites, we are able to find certain references with particular characteristics – fixed, remained, or reassembled. From the old to the new and from the local to the global, the term ‘Shanghai’ is no longer singular, but plural, with a representation of multiple cultures and desires, a representation of its changing self – proud or humiliated, peaceful or turbulent, idealistic or distressed. This theatre never sleeps.

Through a series of curatorial discussions around the process of site visits to the venue WMH, we have invited eight artists to develop new work with different media responding to both the topic of the exhibition and the physical building and its urban environment. These participating artists include those who grew up in Shanghai, those who have migrated to and built their lives in Shanghai, as well as artists domestically from other Chinese cities, and internationally from countries nearby. Each of them will have their instinctive perspective as an insider or an outsider, a host or a guest, an artist or an audience member, to understand or question the urban transformations in the Chinese, Asian and global contexts. In this project, the WMH is no longer an art museum space – a white cube for conventional displays; instead, it returns to its original status as a residential dwelling, a historical building, and a cultural laboratory, for artistic production and dissemination. And at the same time, as one of the most representative cities with its urban and economic landscapes that are constantly shifting, Shanghai has been set as a case study to generate new understandings of contemporary China.

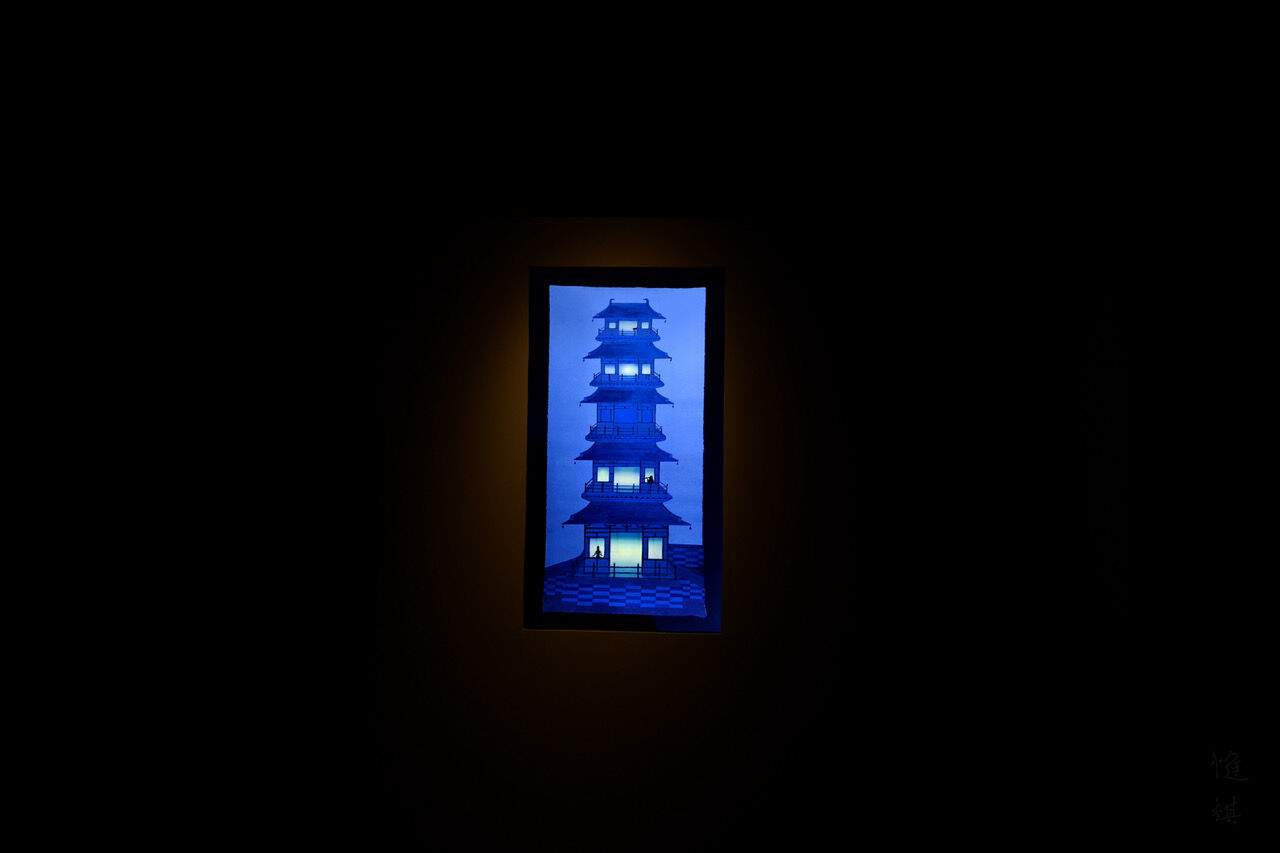

As we enter this site-specific exhibition, Hu Jieming’s series of visual narratives installed on the wooden doors and window panels of the house re-examines the history of Shanghai. Traditional symbols and modern signs are selected and processed through a computer algorithm, which is considered as a ‘collaborator’ in the visual production, to reinvent our understandings of the so-called ‘magical metropolis’, and its cultural and social shifts in the last century. Peng Wei, on the one hand, imitates sections of the patterns of one-hundred-year-old tiles in the house as her unique way to revisit the past, and on the other hand, she projects the vision of a pagoda as a metaphor of everlasting human desires. Further into the building, more artworks are to be experienced. From one room to another, you might hear some old Shanghai jazz or a familiar aria of traditional opera – a mixed soundscape by Yin Yi – providing an immersive experience; you might also encounter Huang Fangling’s work in a performative form, which translates the ordinary to the extraordinary and replays the latest everyday drama in the city; in addition, you might experience disorientation with Yuma Tomiyasu’s installations – pairs of near-identical rooms equipped with similar settings and programmed mechanical devices to suggest someone’s invisible presence, or an eerie theatricality. As we arrive at the central courtyard, Han Kyung-woo’s sculptural work appears geometric, abstract and minimalistic – replicas of the tips of the three iconic skyscrapers in the near distance. Produced in naked concrete, the most common material in the development of urban constructions, the installation seemingly demonstrates a transitional moment of metamorphosis, be it growing or sinking, hopeful or despairing. The courtyard is encircled by handmade doors which were damaged in the Cultural Revolution – all the human figures in the wood carvings having been eradicated. Zhan Wang rubs reliefs of the ruined panels to represent, propagate and problematise the lost. And finally, when we reach the last section of the WMH, Liu Jianhua presents hundreds of empty wooden frames crafted in different shapes and sizes, to capture the nothingness, and to search for and commemorate the unregistered during the processes of the transformations.

In this project, artwork is not being ‘exhibited’, but rather integrated or ‘hidden’ in the building, a long-lived space, as part of its story, or as personal reflections and re-imaginations of the story. Now that the building has experienced all this turbulence, restoration and renovation, and now that the complete historical facts of its story appear to be obscure, wrapped up in layers of cultural, social and political interpretations, our artists have arrived on the scene. We are not acting to conserve the architecture, nor to detect and unveil actualities, but instead to add another layer of wrapping, a curatorial and artistic layer of wrapping, which can fundamentally change the shape and the colour of the story, and redefine it as a legend.