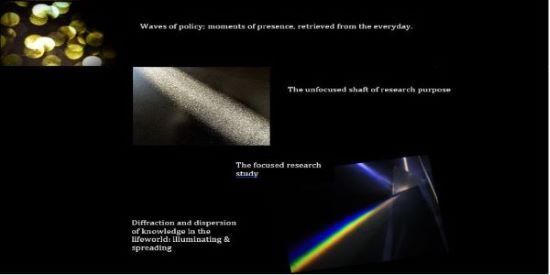

hooks’ subversively human take on the potential of the classroom to be a space that produces, celebrates and nurtures radicalism begs the question: what does this mean for our practice as educational researchers and colleagues in supervisory space? In this piece I will tentatively theorise about doctoral supervision as a place where educational experiences that syncretise personal and wider policy history enter, jumbled and unsorted and how, if a dynamic and adaptable interactive space can be established, this loose unstructured beam of light can be focused (by the student/supervisors) into a beam that, as it hits the lifeworld has the potential to ignite or defract in unpredictable ways.

Over this last twenty-five years it has become clear that an understanding of history is an essential part of the collective consciousness in educational research. In this case, not the history of the Tudors and Stuarts or that of the British Empire spreading its pink eczemic rash across more than a sixth of the earth’s landmass, but recent history: the history that we sense being edited, moulded and interpreted through the simulacra of media with much the same deliberate intent as the curriculum for state schools by government. That is the personal and experiential history that according to Lefebvre (2004: 47) is banished from our consciousness by the tumult and momentum of ‘the present’, a ‘fact and effect of commerce’ that infuses our experience of the everyday. In the face of this perpetual, engulfing present, those of us committed to making sense of education policy and the values and forces that underpin it, need a firm grip on recent history.

John Berger in his novel, G, writes about history like this:

All history is contemporary history: not in the ordinary sense of the word, where contemporary history means the history of the comparatively recent past, but in the strict sense: the consciousness of one’s own activity as one actually performs it. History is thus the self-knowledge of the living mind. For even when the events which the historian studies are events that happened in the distant past, the condition of their being historically known is that they should vibrate in the historian’s mind (Berger, 2012: 54).

All this suggests that we can’t step outside of history: history is both something we are caught up in while also it is of us and authored by us.

For many of us, it seems the rational view of history as applied to education in England and as determining the steady accretion of human progress has taken a battering. Neoliberalisation has functioned in contradictory ways in this regard. On the one hand, the neoliberalisation of education in this country has functioned to feed a ‘cruel optimism’ (Berlant, 2011; Davies and Bansel, 2007) for students who are sold a dream that education is a pathway to secure employment; on the other, neoliberal reforms have proceeded in tandem with the manufacture of contention over what constitutes legitimate knowledge in the field of education. In England, a destructive binarism has been promulgated by the former Secretary of State for Education, among others: of the ‘Blob’ versus government. According to this view, the Blob is an enemy of standards, an enemy of discipline and an enemy of knowledge. In the context of a ‘market review’ of initial teacher education in England, across a thirty-five-year cycle since the introduction of the National Curriculum, we have moved from a government concern to standardise what is learnt by children in (state) schools to the imperative of standardising what student-teachers are taught in universities.

Lefebvre’s thought (Lefebvre, 1991) on spatiality blurs the distinction between mental space and physical space. Central to his Marxist humanist reading of spatiality, is the idea that capital produces, shapes and devours space in particular ways: the way space is conceived of, its symbolic and representative meanings as well as its qualities as lived-in space. Lefebvre saw capitalist relations as producing ‘abstract space’ that tended towards homogenisation and was shaped by its commodified exchange value (Lefebvre, 1991: 49-53). We might see resonance here with the marketisation and massification of HE and the enormous expansion of HE estate that has taken place in England in the last two decades. For Lefebvre this ‘abstract’ space is oppressive and ‘dominated’ by the operation of capital and the relations of commerce.

In Lefebvrian terms, successful supervision involves the co-production of a ‘differential’ educational space that allows for engagement with existing knowledge, criticality in relation to that and, ultimately, the production of new and original knowledge through the students’ research. Lefebvre defines differential space as the potential that is hidden within abstract space. It is produced by the contradictions contained and obscured by abstract space and the possibilities inherent in it. Rather than exchange value, differential space privileges use value and inclusiveness. In other words, differential space is produced when the differences that people bring with them and the meanings they share through these are foregrounded. As such, differential space acknowledges its own affective and reflexive qualities. It can be co-produced by people within abstract space and may be informal and transitory, arising from the inherent rigidity of abstract space that relies on implicit convention and compliance (Leary-Owhin, 2015: 4).

Like all educational space, supervisory space is potentially abstract space. The intimacy and intensity of supervision can be both energising and inhibiting – which means that supervisors bear a responsibility to not only establish the supervisory space as having particular affective qualities but also to foster its co-production involving the doctoral student as an active player. A key aspect of this differentiality lies in its orientation towards knowledge and knowledge production which is closely bound up with a pedagogy.

Supervisory space, when it works well, depends on the doctoral researcher taking charge of the project, finding themselves in it and experiencing the complexity of knowledge production.

We might conclude that supervision offers an example of the importance of conceiving of knowledge production as a social practice: how knowledge is shared, exchanged, encountered, co-produced has a more lasting impact and a longer term effect than what the knowledge is. This flies in the face of the conceptualisation of knowledge that underpins recent policy rhetoric about schools and schooling that champions the transmission of a ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum (Gibb, 2021).

Surely this has been one of the central learning points in education of this last quarter century: that knowledge shapes our societies as much as it shapes our embodied experience and as such it is as subject to the monstrous destruction, deformation and waste as every other aspect of human life under the sway of capital. This understanding must shape how we aim to co-produce differential supervisory space.

The images suggest a way of conceptualising doctoral research through the metaphor of light and light particles. The supervisory process begins with an unfocused shaft of light, made up of unreflected-upon particles / waves of temporal experience; in co-produced differential supervisory space, this broad shaft is focused into a beam of light: cohesive, illuminating; this beam then is refracted on entry back into the lifeworld as knowledge with the potential to ignite or defract in unpredictable ways.

Credit for the final image: "Light dispersion of a mercury-vapor lamp with a flint glass prism IPNr°0125.jpg" by D-Kuru is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.