Threshold Concepts (TCs) can be seen as an important aspect of the teaching and learning cycle. Although there has been more international interest in this area during recent years, it has been largely focused within the Higher Education domain. What is clear is that thinking around this area does not seem to have ventured into secondary school literature, particularly within the field of music education. As such, as a contribution to literature in this area, this blog focuses on Key Stage 3 group composing.

Threshold Concept & Formative assessment

Although there is some debate over how the term “Threshold Concept” (TC) can be defined, Jan Meyer and Ray Land (two academics who have done much of the original work on TCs) say that it can refer to when learners, for example, ‘get stuck’ (Meyer and Land, 2006, p. i) at particular points in their learning of the curriculum and, therefore, require some sort of knowledge in order to progress. The identification and potential problematisation of TCs also can be linked with formative assessment literature.

Formative assessment, when used effectively, has been proved to have a significant impact on student learning (Black and Wiliam, 1998). As such, engaging in a formative assessment process (where information about pupil learning is elicited and acted upon by teachers and/or learners) can be a powerful process to cross a TC. Again, definitions are important; there is no internationally-agreed definition as to what “formative assessment” is. That said, within the United Kingdom, the term tends to be built upon the pioneering work of Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam through their publication Inside the Black Box (among others) who state that formative assessment can be defined as:

all those activities undertaken by teacher, and/or their students to modify teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged (1998: 8).

Data Collection

To explore the notion of TCs and formative assessment in Key Stage 3 composing, qualitative and quantitative data were taken from my current, in-progress (as of June 2020) PhD work. Here, observational data were collected from three case-study schools, labelled A-C, by video-recording composing sessions throughout a unit of study. School “A” was a pilot, so only video-recorded data were collected. For Schools “B” and “C”, though, semi-structured interviews were also carried out: one with the music teacher, the other with the group of students who acted as a focus group.

Data collection took place in schools located in the English Midlands (details are summarised in the table below). All schools were mixed-gender and non-selective secondary schools with each of the music teachers working in already established, single-person departments. Student composing groups were selected by the teachers, as was normal practice.

|

|

|

Case-study A |

Case-study B |

Case-study C |

|

Teacher-participants |

Gender of Teacher |

Male |

Female |

Female |

|

Number of years teaching |

10 |

4 |

27 |

|

|

Learner-participants |

School year group |

Year 9 (ages 13-14) |

Year 8 (ages 12-13) |

Year 7 (ages 11-12)

|

The composing tasks were constructed by the music teacher, as was normal practice:

School “A”: Compose a piece of music, in any style, which is clearly built around rondo form.

School “B”: Compose a rap or song (or both) following rondo form which includes the chords C, D, F and G majors, as well as lyrics.

School “C”: Create a short piece in Ternary Form based on an ostinato. At least one ostinato needs to be rhythmic and one must be melodic. Think carefully about the elements of music and how they can be used effectively.

Findings

Following the process of data collection, analysis and coding, four TCs were identified and will be briefly discussed in turn. Within each TC identified, I have also provided a short discussion as to how formative assessment was, or could have been, a key process for a concept being crossed.

TC 1: Establishing a starting point for composing

In School “A”, a TC was clear at the very beginning of the composing process and came as a starting point for composing where the group appeared to struggle on deciding on what musical style they would compose their rondo form piece in (since this was free choice) as well as the initial ideas on which to build. To cross this threshold, one student used her mobile phone to search for music for the group to listen to on YouTube. In other words, the use of the mobile phone as a key tool for learning helped make the start of the composing process easier for these students. It was through students using the mobile phone to elicit information (musical inspiration) and then actively using that information to being the composing process that formative assessment can be said to have taken place.

TC 2: Establishing a starting point for lyric writing

In School “B”, composing lyrics proved problematic; a significant amount of composing time was taken up with the group discussing what lyrics should go into their composition. The amount of time spent in this phase is shown in the following table:

|

Composing session |

Amount of composing time (%) the group spent discussing lyrics |

|

Session 3 |

43% |

|

Session 4 |

67% |

|

Session 5 |

46% |

What is interesting is that, during the post-study group interview, the students commented that listening to model examples of previous student work and access to YouTube would have been very beneficial to them in crossing the TC of lyric writing. This makes an interesting link back to students in school “A” (above) where it was found that the formative use of the mobile phone seen as a key process for crossing the TC.

In this context, however, it could be argued that effective formative assessment was hindered because of the lack of learners’ knowledge and understanding in this important area. As such, this raises some important questions about the need to establish the level of students’ prior knowledge prior to beginning a learning task.

TC 3: Knowing and being able to play chords

This TC refers to when a student was having difficulty with knowing the notes within chords and being able to play chord sequences on the piano as part of the group composition. To cross this individual’s threshold, another student (a fellow pianist) support him.

Through several spoken and musical exchanges and modelling it became clear that the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978, 1987) was at work. In this case, the dialogue and modelling exchanges, as formative strategies, helped the TC being crossed and, as a result, the student then not only knew the notes in chords and was able to play chord sequences, but was able to make a valuable contribution, through playing the piano, within the group’s composition. It should be pointed out, however, that although, in this context, the individual student’s composing potential was not necessarily exceeded, his performing ability, through formative assessment, was.

TC 4: The potential for creating TC

During five, consecutive composing sessions in School “C”, the focus group did not appear to encounter any TCs to cross. This is important. The group worked in a highly efficient way from the beginning to the end of the unit of study and created a composition which was of excellent quality. In this example, the TC perhaps needs to be more teacher-focused than individual learner or group-focused per se. For example, as part of reflective teacher practice, there might have been opportunities where the group could have been further challenged through the creating of TCs. This could be seen as an important part of lesson-by-lesson formative assessment as learners follow the trajectory from novice to more skilled musicians. Although it cannot be claimed that learners, in this context, did not grow as more knowledgeable and skilled musicians; rather to question as to whether no TCs being created was a “missed opportunity” given the time they had.

Conclusion:

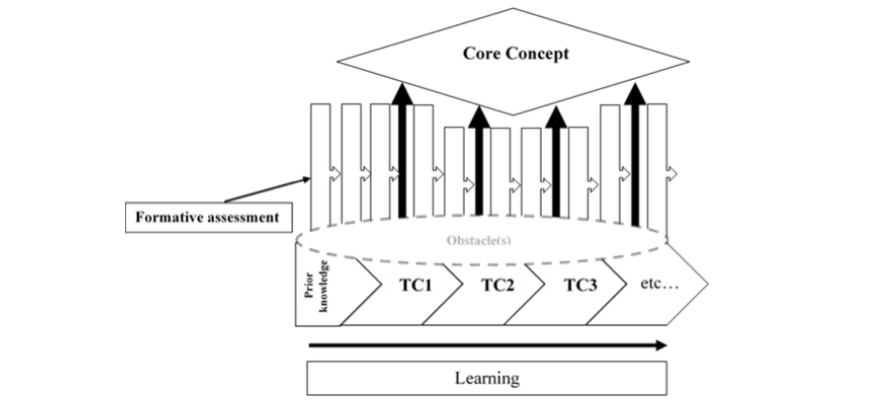

From the data cited above a suitable model can be drawn up.

In this figure, the process begins with establishing what prior knowledge learners have within the overarching core concept. For example, what prior knowledge do learners have about lyric writing and applying them into composing? This feeds into related and sequential threshold concepts (which might be pre-planned by the teacher, encountered during the ongoing learning process, and/or, in some cases, additional ones may be created throughout the unit of study). Formative assessment is identified and is shown as a key process for crossing TCs throughout ongoing learning. For example, drawing on the data cited above effective formative assessment strategies could take the form of: using mobile phones; peer-to-peer support; or exemplar work where information from them can be elicited and, more importantly, used to help move the composing process forward. The success of formative assessment, however, can be subject to potential obstacles. Such obstacles might include, for example: group dynamics, disruptive behaviour, teacher or learner absence(s), meeting specific learning needs, learning resources/equipment, and time constraints.

In this figure, the process begins with establishing what prior knowledge learners have within the overarching core concept. For example, what prior knowledge do learners have about lyric writing and applying them into composing? This feeds into related and sequential threshold concepts (which might be pre-planned by the teacher, encountered during the ongoing learning process, and/or, in some cases, additional ones may be created throughout the unit of study). Formative assessment is identified and is shown as a key process for crossing TCs throughout ongoing learning. For example, drawing on the data cited above effective formative assessment strategies could take the form of: using mobile phones; peer-to-peer support; or exemplar work where information from them can be elicited and, more importantly, used to help move the composing process forward. The success of formative assessment, however, can be subject to potential obstacles. Such obstacles might include, for example: group dynamics, disruptive behaviour, teacher or learner absence(s), meeting specific learning needs, learning resources/equipment, and time constraints.

Considerations from the Research

As a result of this exploration several key considerations arise for those working in schools:

Considerations for teachers:

When planning composing tasks:

- consider what prior knowledge learners already possess before they begin a composing journey. What formative strategies might students require to support the generation of their ideas?

- consider what new TCs learners can be challenged with during a lesson (where appropriate). What formative strategies might they require to support them with this.

When organising composing groups:

- consider to what extent individual learners working within groups are able to support each other, in addition teacher support, during the composing process.

When listening to and giving feedback on in-process group composing:

- consider what additional TCs might be created, for some learners. What additional formative strategies might they require to support them with this.

Considerations for school leaders:

- How might formative assessment practice be further developed to support teachers in identifying and resolving TCs?.

Considerations for school leaders and policy makers:

- Consider how digital tools like mobile phones, for example, can be used effectively and safely in the classroom and how they might be successfully monitored to act as an effective learning device.

References:

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998) Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. London, UK: King's College School of Education.

Meyer, J. and, Land, R. (2006) Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. In: J. Meyer and R. Land (eds.), Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. (1978) Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1987) Thinking and speech. In: The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. London, UK: Blackwell.