How do we use our class-time? How do we prepare to teach new subject matter? How do we find our identity in areas not our own? The need for trial and error and the spirit of reinvention if we are to get better. A plea for sharing and purpose rather than just internet research and virtual meetings. This sounds very grand, but this blog is actually about re-connecting with what matters after a time of different connectivity but also years of being given texts to teach which mean little initially although they have been chosen for their cultural impact.

"I know that it is not the English language that hurts me, but what the oppressors do with it, how they shape it to become a territory that limits and defines, how they make it a weapon that can shame, humiliate, colonize” (hooks, 1994).

Here weaponising language seems a means to belittle and oppress and interestingly in this quotation bell hooks does not particularise the injury. As a thinker moving towards what we now know as intersectionality with her feminist theory which shows how race, gender, class can all be means of oppression, bell hooks adopts a pen name with capitalisation for the start of proper nouns, which immediately makes her stand out. Some think it is a denunciation of the male rules of language which carry certain prescriptions. Interestingly, however, she said that she took the name not to focus on her own identity, but it is a way of declaring her writing/thinking self as well as her familial history and female legacy. In getting away from Gloria Watkins and any father associations the name carries, she celebrates her grandmother who also had a male-derived surname. But then we know she picks and chooses: Teaching to Transgress is “Copyright © 1994 Gloria Watkins.

Black writers changing their name, taking on a new identity is nothing new. Did you know that Chloe Ardelia Wofford is more readily recognised as Toni Morison? As in Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison? Of course, Toni Morrison’s change owes much to a more traditional female transformation: becoming a wife. However, in Toni’s case, she was only married for six years (1958 – 1964) and her first literary success was in 1970 with The Bluest Eye. As for the switch from Chloe to Toni, that occurred when she moved to Howard University and found people had problems pronouncing her name. And Ardelia rather got lost along the way when she took on Anthony as her confirmation name at the age of twelve. Names as an aspect of language can be shifting and elusive.

But what of bell hooks’ quotation? I am particularly interested in the “shame, humiliate, colonize” aspect of it. It suggests English Language can be used to make one feel lesser, less capable, less good so maybe by association bad. In some ways I think the world has moved somewhat, which is partly an effect of being woke privilege where we privilege black/youth/gay/feminist/etc experience and accompanying language use and employ cancel culture to denounce former icons who drift into political incorrectness (J.K. Rowling, John Cleese, Ricky Gervais, Dave Chapelle and so on); but also multi-culturalism. The latter is a big word, but I remember starting small: sparks rather than fires.

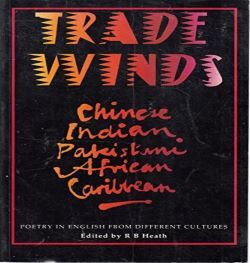

In 1996, I became a Head of English. I inherited a department which had a compilation poetry text called Trade Winds used in the lower school (KS3). A recommendation, no one really knew what to do with and the department was still years away from schemes of work and other collective prescriptivism. I ascertained that colleagues dipped into it and taught their favourite texts, but the amount of time spent with the text was equally personal choice. It was trendy poetry perhaps, but I got no sense of anyone really enjoying it despite the righteous we-are-broadening-horizons rationalising.

The anthology contained biographies and teaching ideas, but these were not given much attention. Colleagues liked that it was a different demand to Robert Browning’s “The Pied Piper of Hamlyn”, a Year 7 challenge (a long poem – gosh!). I decided that we should study some of the different forms and illustrate them alongside Sandy Brownjohn poetry exercises such as limericks, tankas, rengas and naga-Utas; look at two of the cultural areas with some depth and compare and contrast some concerns and issues; and also demonstrate some different types of verse (narrative, argument, reflective, etc). Colleagues still possessed masses of freedom in terms of what they taught, but we gained some focus in terms of departmental and corridor discussions (Are you really doing the African selection? How are you finding the Chinese cluster?) However, we also started to define some must-teach poems such as “Night of the Scorpion” by Nissim Ezekiel.

This worked for us as some of the Trade Winds poems fetched up in the AQA Anthology Poems From Other Cultures and Traditions which interestingly changed its designation to Poems from Different Cultures. (Universities might consider the concept of “othering” as a valid avenue of pursuit, but maybe a minefield for schools.) The texts offered were in some cases hard to teach and a tough ask for teenagers not overly sold on poetry anyway. I remember finding “Search for My Tongue” particularly annoying, not least because it meant correcting “Tonge” and “gujerati” so many, many times in essays. However, the main problem was that in the middle there is Gujarati section followed by an English translation. I was never happy reading the poem out aloud because of the “foreign” section, but also was never sure whether the English translation was a substitute for the Gujarati version and should be disregarded or whether one should just note the Gujarati section, but not make it part of any reading as one would inevitably do it a disservice.

After a few years, I found a Gujarati speaker among my pupils and she read the tricky middle section – a big improvement, but, of course, she did not want to read the whole poem which frustrated the message somewhat as it was about a persona caught between cultures and losing native language facility as (s)he became assimilated in another way of thinking. However, small victory, little fire.

Later my centre switched to OCR and picked up a different poetry collection for GCSE: Towards a World Unknown which has an intriguing title which is mainly positive suggesting forward movement, but also a touch concerning as the unknown world might indicate we have not travelled that far multiculturally. This English Literature collection has fewer poems from other cultures; but one I struggled with was “Partition” by Sujata Bhatt (her again) which dealt with the partitioning of India (obvs) but seemed very disconnected and recalled some quiet domestic events. The first time I taught it was very much a so-what? poem. But, after a year, I realised the way into it was herstory and it became a favourite teach of mine. Flame on.

However, while it’s good to get fired up and ignite adolescent minds to good poetry, I’m not convinced we’ve got the practice here right. Time to transgress and go for five:

- Exam boards produce biographies to accompany poetry selections. Is this what we need? How much of the bell hooks and Toni Morrison name history stuck at the start of this blog?

- Single poems are single poems at the end of the day and it’s more rewarding to have little clusters of poems such as I built up after teaching single poems over many years – groups of poems by John Agard, Grace Nichols, Imtiaz Dharker and, of course, Sujata Bhatt, But others too.

- Recordings and animations are good for hooking students into poetry, but they need to be more than biographical accompaniments. Poems are more than context. Focus on words rather than delivery.

- In the first few years of any new anthology, teachers teach poems that they have not totally assimilated. I am putting my hand up for this past bad transgression. As we move back to a more open world, there needs to be more opportunities for teachers to meet and discuss material as there were in the good old days. Zoom and MS Teams just don’t cut it. Controversy!

- Teach multicultural poems as political statements rather than works of art – language, as Toni Morrison said, “as an agency and as an act with consequences” (Morrison, 1993).