Blog

For Mental Health Awareness Day, Professor of Occupational Health Psychology, Craig Jackson, looks at the complexity of suicidal behaviour and how mental health problems are not the only reason why some people choose to end their lives. Suicide is a complicated phenomenon, but the reasons underlying such actions might be simple to understand.

There has no doubt been an increase in the willingness for sensitive public debate around the causes and impacts of living with depression or anxiety and other mental health problems. With this understanding has come greater sympathy for those living with long-term mental health problems, those who have survived suicidal attempts, and those who did not. There is greater public discourse around de-stigmatising suicide, but it should be remembered that many suicidal deaths and attempts occur without a background of chronic depression or anxiety in individuals’ backgrounds.

Suicide is a very complex area to understand, and is almost impossible to predict reliably. However there are usually several factors that can influence individuals (and sometimes groups) and their suicidal thoughts and actions. Such influences include a range of learned behaviours, media influences, previous experiences, difficult life situations, attitudes, and mental state, as well as practical considerations such as having the opportunity, space, and means with which to take one’s life. The vast majority of suicidal deaths have a complex mix of such factors in the background, as well as ongoing difficult situations and a bleak outlook on life. Official data on suicides in the UK can sometimes be unreliable and patchy, and is often influenced by coroners' courts and the decisions made therein (the source of the data used by the Office of National Statistics).

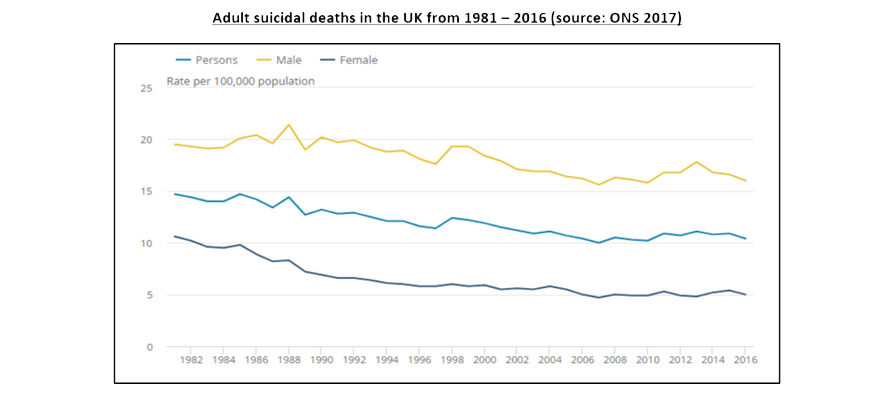

Suicidal deaths in the UK fell year on year from the early 1980s, reaching an all-time low (of 10 suicidal deaths per 100,000 of the population) in 2007 and then steadily increased year on year since 2008 as a result of the financial crash. Current suicide rates in the UK do now seem to be dropping again, almost to the same figure as in 2007, which is approximately at 8000 suicidal deaths each year.

Whenever large-scale reviews of suicide data are undertaken, the results often change drastically with each review, giving an often confusing and contradictory overview. However, some of the aspects about suicide that seem to be consistent over time are:

- Suicidal individuals have often reached a position where they feel that death is preferable to the pain and difficulty of continuing to live.

- When someone has thought, planned and over-focused on their own suicide, it can be virtually impossible to stop them killing themselves if they are determined.

- Suicide does not just impact those with ongoing mental health problems or with a history of previous mental health issues, and many suicidal deaths occur among those who have lived free from depression or anxiety.

- The greatest predictor of suicidal death is having made a previous (unsuccessful) attempt. The notion that someone who survives a suicide attempt will be fine as they have “got it out of their system” is a dangerous one.

- Males account for 75% of all suicidal deaths, and this is typically due to them using high-impact, instantaneous and visceral methods more than females.

- Males aged 45-60 are the biggest at-risk group (up until three years ago it was males aged 18-25), with suicide still the biggest killer of the under-50s.

- Suicide attempts are not simply due to having a stressful day or a tough time at work – those situations are important but they do not represent everything – and suicide should be understood as a complex end-stage behaviour.

- Individuals with plenty of life options – education, employment, family, and partners – are not immune from committing suicide, and it is not a phenomenon that just effects those at the “bottom of the pile” in society.

- However, people with low pay and low job security are at greater risk of suicidal death, and suicide risk is higher for those living in socially poorer areas than affluent areas.

- There is a clear link between some occupations and suicide, although it must be remembered that people with a higher risk of suicide may be more likely to choose certain professions.

- Knowledge of suicidal methods increases an individual’s risk of attempting suicide, and having access to lethal means also makes suicidal deaths more likely. Prurient reporting of suicides in the media is also known to increase this risk.

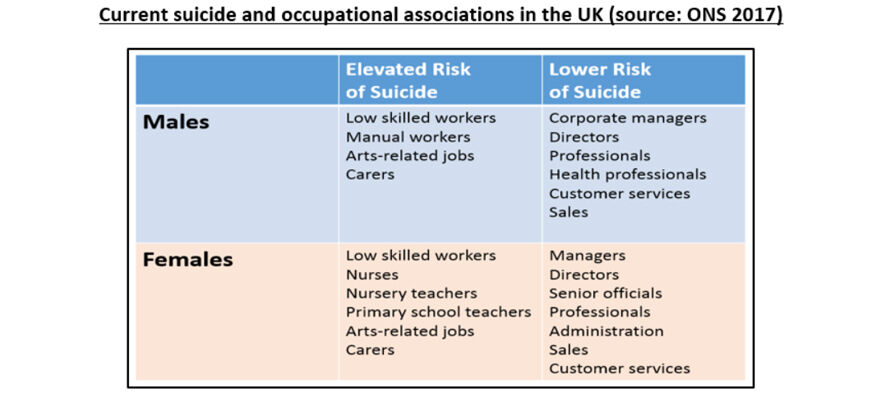

The latest ONS data concerning suicide and occupation in the UK (2017) has shown some interesting trends. Males with an elevated risk of suicide include low-skilled workers and manual workers, those with arts-related jobs, and those in the caring professions. Females with an increased suicide risk include low-skilled workers, nurses, nursery teachers, primary school teachers, carers and those with arts-related jobs. Such occupations can be regarded as “suicidogenic”. Occupations that are seemingly protective against suicide risk in the UK are very similar for both males and females – including managers, directors, professionals, health professionals, customer services and sales. Administrative work was found to be suicide–protective in females only.

These categories often change readily, and only five years ago the occupations with the greatest risk of suicide were vets, dentists, farmers and pharmacists, but increased education and health surveillance led to these occupations becoming less suicidogenic. Now it is the turn of the manual and unskilled workers to be looked after, but perhaps it is not the occupation per se that is related to suicide levels, but a crisis of meaninglessness in modern working. We need to ask if workers, regardless of their job-type, have meaningful lives: do their jobs give them purpose; do they have positive relationships; do they feel worthwhile and valued by what they do and can this be improved somehow? Any future suicide epidemics may not be related to increased levels of mental health problems, but perhaps due to a crisis of existentialism related to meaningless working.